Xunlei Accelerator (迅雷客户端) a.k.a. Xunlei Thunder by the China-based Xunlei Ltd. is a wildly popular application. According to the company’s annual report 51.1 million active users were counted in December 2022. The company’s Google Chrome extension 迅雷下载支持, while not mandatory for using the application, had 28 million users at the time of writing.

迅雷加速器(迅雷客户端)又名迅雷雷霆,由总部位于中国的迅雷有限公司开发,是一款广受欢迎的应用程序。根据该公司的年度报告,2022 年 12 月统计了 5110 万活跃用户。该公司的 Google Chrome 扩展迅雷下载支持,虽然不是使用该应用程序的强制性要求,但在撰写本文时拥有 2800 万用户。

I’ve found this application to expose a massive attack surface. This attack surface is largely accessible to arbitrary websites that an application user happens to be visiting. Some of it can also be accessed from other computers in the same network or by attackers with the ability to intercept user’s network connections (Man-in-the-Middle attack).

我发现这个应用程序暴露了一个巨大的攻击面。应用程序用户碰巧正在访问的任意网站在很大程度上可以访问此攻击面。其中一些也可以从同一网络中的其他计算机访问,或者由能够拦截用户网络连接的攻击者访问(中间人攻击)。

It does not appear like security concerns were considered in the design of this application. Extensive internal interfaces were exposed without adequate protection. Some existing security mechanisms were disabled. The application also contains large amounts of third-party code which didn’t appear to receive any security updates whatsoever.

在此应用程序的设计中似乎没有考虑安全问题。大量的内部接口在没有充分保护的情况下暴露出来。一些现有的安全机制被禁用。该应用程序还包含大量第三方代码,这些代码似乎没有收到任何安全更新。

I’ve reported a number of vulnerabilities to Xunlei, most of which allowed remote code execution. Still, given the size of the attack surface it felt like I barely scratched the surface.

我向迅雷报告了许多漏洞,其中大部分允许远程执行代码。尽管如此,考虑到攻击面的大小,我感觉我几乎没有触及表面。

Last time Xunlei made security news, it was due to distributing a malicious software component. Back then it was an inside job, some employees turned rouge. However, the application’s flaws allowed the same effect to be easily achieved from any website a user of the application happened to be visiting.

迅雷上一次做安全新闻,是因为分发了一个恶意软件组件。那时候是内部工作,有的员工胭脂。但是,该应用程序的缺陷允许从该应用程序的用户碰巧访问的任何网站轻松实现相同的效果。

Contents 内容

What is Xunlei Accelerator?

什么是迅雷加速器?

Wikipedia lists Xunlei Limited’s main product as a Bittorrent client, and maybe a decade ago it really was. Today however it’s rather difficult to describe what this application does. Is it a download manager? A web browser? A cloud storage service? A multimedia client? A gaming platform? It appears to be all of these things and more.

维基百科将迅雷有限公司的主要产品列为 Bittorrent 客户端,也许十年前确实如此。然而,今天很难描述这个应用程序的作用。是下载管理器吗?网络浏览器?云存储服务?多媒体客户端?游戏平台?它似乎是所有这些东西,甚至更多。

It’s probably easier to think of Xunlei as an advertising platform. It’s an application with the goal of maximizing profits through displaying advertising and selling subscriptions. As such, it needs to keep the users on the platform for as long as possible. That’s why it tries to implement every piece of functionality the user might need, while not being particularly good at any of it of course.

将迅雷视为一个广告平台可能更容易。这是一个应用程序,其目标是通过显示广告和销售订阅来最大化利润。因此,它需要尽可能长时间地将用户留在平台上。这就是为什么它试图实现用户可能需要的每一项功能,当然也不是特别擅长其中任何一个。

So there is a classic download manager that will hijack downloads initiated in the browser, with the promise of speeding them up. There is also a rudimentary web browser (two distinctly different web browsers in fact) so that you don’t need to go back to your regular web browser. You can play whatever you are downloading in the built-in media player, and you can upload it to the built-in storage. And did I mention games? Yes, there are games as well, just to keep you occupied.

因此,有一个经典的下载管理器可以劫持浏览器中启动的下载,并承诺加快速度。还有一个基本的网络浏览器(实际上是两个截然不同的网络浏览器),因此您无需返回常规网络浏览器。您可以在内置媒体播放器中播放正在下载的任何内容,也可以将其上传到内置存储。我有没有提到游戏?是的,也有游戏,只是为了让你忙得不可开交。

Altogether this is a collection of numerous applications, built with a wide variety of different technologies, often implementing competing mechanisms for the same goal, yet trying hard to keep the outward appearance of a single application.

总而言之,这是众多应用程序的集合,这些应用程序使用各种不同的技术构建,通常为同一目标实现竞争机制,但努力保持单个应用程序的外观。

The built-in web browser

内置 Web 浏览器

The trouble with custom Chromium-based browsers

基于 Chromium 的自定义浏览器的麻烦

Companies love bringing out their own web browsers. The reason is not that their browser is any better than the other 812 browsers already on the market. It’s rather that web browsers can monetize your searches (and, if you are less lucky, also your browsing history) which is a very profitable business.

公司喜欢推出自己的网络浏览器。原因不在于他们的浏览器比市场上已有的其他 812 浏览器更好。相反,网络浏览器可以通过您的搜索获利(如果您不那么幸运,还可以通过您的浏览历史记录获利),这是一项非常有利可图的业务。

Obviously, profits from that custom-made browser are higher if the company puts as little effort into maintenance as possible. So they take the open source Chromium, slap their branding on it, maybe also a few half-hearted features, and they call it a day.

显然,如果公司尽可能少地投入维护精力,那么定制浏览器的利润会更高。因此,他们采用了开源的 Chromium,在上面打上了自己的品牌,也许还有一些半心半意的功能,然后他们就收工了。

Trouble is: a browser has a massive attack surface which is exposed to arbitrary web pages (and ad networks) by definition. Companies like Mozilla or Google invest enormous resources into quickly plugging vulnerabilities and bringing out updates every six weeks. And that custom Chromium-based browser also needs updates every six weeks, or it will expose users to known (and often widely exploited) vulnerabilities.

麻烦的是:浏览器具有巨大的攻击面,根据定义,该攻击面暴露在任意网页(和广告网络)中。像Mozilla或Google这样的公司投入了大量资源来快速堵塞漏洞,并每六周发布一次更新。而且,基于Chromium的自定义浏览器也需要每六周更新一次,否则它将使用户暴露于已知的(并且经常被广泛利用的)漏洞。

Even merely keeping up with Chromium development is tough, which is why it almost never happens. In fact, when I looked at the unnamed web browser built into the Xunlei application (internal name: TBC), it was based on Chromium 83.0.4103.106. Being released in May 2020, this particular browser version was already three and a half years old at that point. For reference: Google fixed eight actively exploited zero-day vulnerabilities in Chromium in the year 2023 alone.

即使只是跟上 Chromium 的开发也很困难,这就是为什么它几乎从未发生过。事实上,当我查看 Xunlei 应用程序内置的未命名 Web 浏览器(内部名称:TBC)时,它基于 Chromium 83.0.4103.106。这个特定的浏览器版本于 2020 年 5 月发布,当时已经有三年半的历史了。供参考:仅在 2023 年,谷歌就修复了 Chromium 中八个被积极利用的零日漏洞。

Among others, the browser turned out to be vulnerable to CVE-2021-38003. There is this article which explains how this vulnerability allows JavaScript code on any website to gain read/write access to raw memory. I could reproduce this issue in the Xunlei browser.

除其他外,该浏览器被证明容易受到 CVE-2021-38003 的攻击。本文解释了此漏洞如何允许任何网站上的 JavaScript 代码获得对原始内存的读/写访问权限。我可以在迅雷浏览器中重现这个问题。

Protections disabled 已禁用保护

It is hard to tell whether not having a pop-up blocker in this browser was a deliberate choice or merely a consequence of the browser being so basic. Either way, websites are free to open as many tabs as they like. Adding --autoplay-policy=no-user-gesture-required command line flag definitely happened intentionally however, turning off video autoplay protections.

很难说在这个浏览器中没有弹出窗口阻止程序是一个故意的选择,还是仅仅是因为浏览器太基础了。无论哪种方式,网站都可以自由打开任意数量的标签。但是,添加 --autoplay-policy=no-user-gesture-required 命令行标志肯定是故意发生的,关闭了视频自动播放保护。

It’s also notable that Xunlei revives Flash Player in their browser. Flash Player support has been disabled in all browsers in December 2020, for various reasons including security. Xunlei didn’t merely decide to ignore this reasoning, they shipped Flash Player 29.0.0.140 (released in April 2018) with their browser. Adobe support website lists numerous Flash Player security fixes published after April 2018 and before end of support.

Censorship included

Interestingly, Xunlei browser won’t let users visit the example.com website (as opposed to example.net). When you try, the browser redirects you to a page on static.xbase.cloud. This is an asynchronous process, so chances are good that you will catch a glimpse of the original page first.

Automated translation of the text: “This webpage contains illegal or illegal content and access has been stopped.”

文本的自动翻译:“此网页包含非法或非法内容,访问已停止。

As it turns out, the application will send every website you visit to an endpoint on api-shoulei-ssl.xunlei.com. That endpoint will either accept your choice of navigation target or instruct to redirect you to a different address. So when to navigate to example.com the following request will be sent:

事实证明,该应用程序会将您访问的每个网站发送到 api-shoulei-ssl.xunlei.com .该终结点将接受您选择的导航目标,或指示将您重定向到其他地址。因此,何时导航到 example.com 将发送以下请求:

POST /xlppc.blacklist.api/v1/check HTTP/1.1

Content-Length: 29

Content-Type: application/json

Host: api-shoulei-ssl.xunlei.com

{"url":"http://example.com/"}

And the server responds with:

服务器响应:

{

"code": 200,

"msg": "ok",

"data": {

"host": "example.com",

"redirect": "https://static.xbase.cloud/file/2rvk4e3gkdnl7u1kl0k/xappnotfound/#/unreach",

"result": "reject"

}

}

Interestingly, giving it the address http://example.com./ (note the trailing dot) will result in the response {"code":403,"msg":"params error","data":null}. With the endpoint being unable to handle this address, the browser will allow you to visit it.

Native API

In an interesting twist, the Xunlei browser exposed window.native.CallNativeFunction() method to all web pages. Calls would be forwarded to the main application where any plugin could register its native function handlers. When I checked, there were 179 such handlers registered, though that number might vary depending on the active plugins.

有趣的是,迅雷浏览器向所有网页公开 window.native.CallNativeFunction() 了方法。调用将被转发到主应用程序,任何插件都可以在其中注册其本机函数处理程序。当我检查时,有 179 个这样的处理程序注册,尽管这个数字可能因活动插件而异。

Among the functions exposed were ShellOpen (used Windows shell APIs to open a file), QuerySqlite (query database containing download tasks), SetProxy (configure a proxy server to be used for all downloads) or GetRecentHistorys (retrieve browsing history for the Xunlei browser).

公开的功能包括 ShellOpen (使用 Windows shell API 打开文件)、 QuerySqlite (查询包含下载任务的数据库)、 SetProxy (配置用于所有下载的代理服务器)或 GetRecentHistorys (检索迅雷浏览器的浏览历史记录)。

My proof-of-concept exploit would run the following code:

我的概念验证漏洞将运行以下代码:

native.CallNativeFunction("ShellOpen", "c:\\windows\\system32\\calc.exe");

This would open the Windows Calculator, just as you’d expect.

这将打开 Windows 计算器,正如您所期望的那样。

Now this API was never meant to be exposed to all websites but only to a selected few very “trusted” ones. The allowlist here is:

现在,这个 API 从来都不是要向所有网站公开的,而只是要向少数几个非常“受信任”的网站公开。此处的允许列表是:

[

".xunlei.com",

"h5-pccloud.onethingpcs.com",

"h5-pccloud.test.onethingpcs.com",

"h5-pciaas.onethingpcs.com",

"h5-pccloud.onethingcloud.com",

"h5-pccloud-test.onethingcloud.com",

"h5-pcxl.hiveshared.com"

]

And here is how access was being validated:

function isUrlInDomains(url, allowlist, frameUrl) {

let result = false;

for (let index = 0; index < allowlist.length; ++index) {

if (url.includes(allowlist[index]) || frameUrl && frameUrl.includes(allowlist[index])) {

result = true;

break;

}

}

return result;

}

As you might have noticed, this doesn’t actually validate the host name against the list but looks for substring matches in the entire address. So https://malicious.com/?www.xunlei.com is also considered a trusted address, allowing for a trivial circumvention of this “protection.”

Getting into the Xunlei browser

Now most users hopefully won’t use Xunlei for their regular browsing. These should be safe, right?

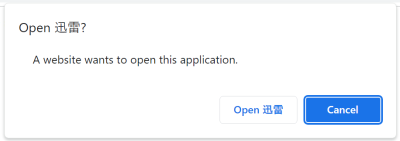

Unfortunately not, as there is a number of ways for webpages to open the Xunlei browser. The simplest way is using a special thunderx:// address. For example, thunderx://eyJvcHQiOiJ3ZWI6b3BlbiIsInBhcmFtcyI6eyJ1cmwiOiJodHRwczovL2V4YW1wbGUuY29tLyJ9fQ== will open the Xunlei browser and load https://example.com/ into it. From the attacker’s point of view, this approach has a downside however: modern browsers ask the user for confirmation before letting external applications handle addresses.

There are alternatives however. For example, the Xunlei browser extension (28 million users according to Chrome Web Store) is meant to pass on downloads to the Xunlei application. It could be instrumented into passing on thunderx:// links without any user interaction however, and these would immediately open arbitrary web pages in the Xunlei browser.

More ways to achieve this are exposed by the XLLite application’s API which is introduced later. And that’s likely not even the end of it.

The fixes 修复

While Xunlei never communicated any resolution of these issues to me, as of Xunlei Accelerator 12.0.8.2392 (built on February 2, 2024 judging by executable signatures) several changes have been implemented. First of all, the application no longer packages Flash Player. It still activates Flash Player if it is installed on the user’s system, so some users will still be exposed. But chances are good that this Flash Player installation will at least be current (as much as software can be “current” three years after being discontinued).

虽然迅雷从未向我传达过这些问题的任何解决方案,但从迅雷加速器 12.0.8.2392(根据可执行签名判断,于 2024 年 2 月 2 日构建)开始,已经实施了几项更改。首先,该应用程序不再打包 Flash Player。如果 Flash Player 安装在用户的系统上,它仍会激活它,因此某些用户仍会暴露。但是,这个Flash Player安装很有可能至少是最新的(就像软件在停产三年后可以是“最新的”一样)。

The isUrlInDomains() function has been rewritten, and the current logic appears reasonable. It will now only check the allowlist against the end of the hostname, matches elsewhere in the address won’t be accepted. So this now leaves “only” all of the xunlei.com domain with access to the application’s internal APIs. Any cross-site scripting vulnerability anywhere on this domain will again put users at risk.

isUrlInDomains() 函数已被重写,当前逻辑显得合理。它现在只会根据主机名的末尾检查允许列表,不接受地址中其他地方的匹配项。因此,现在“仅”保留所有 xunlei.com 域可以访问应用程序的内部 API。此域上任何位置的任何跨站点脚本漏洞都将再次使用户面临风险。

The outdated Chromium base appears to remain unchanged. It still reports as Chromium 83.0.4103.106, and the exploit for CVE-2021-38003 still succeeds.

过时的 Chromium 基础似乎保持不变。它仍然报告为 Chromium 83.0.4103.106,并且对 CVE-2021-38003 的利用仍然成功。

The browser extension 迅雷下载支持 also received an update, version 3.48 on January 3, 2024. According to automated translation, the changelog entry for this version reads: “Fixed some known issues.” The fix appears to be adding a bunch of checks for the event.isTrusted property, making sure that the extension can no longer be instrumented quite as easily. Given these restrictions, just opening the thunderx:// address directly likely has higher chances of success now, especially when combined with social engineering.

浏览器扩展迅雷下载支持也于 2024 年 1 月 3 日收到了更新,版本为 3.48。根据自动翻译,此版本的更新日志条目为:“修复了一些已知问题。该修复程序似乎为 event.isTrusted 属性添加了一堆检查,确保扩展不再那么容易地检测。鉴于这些限制,现在直接打开 thunderx:// 地址可能有更高的成功机会,尤其是当与社会工程相结合时。

The main application

Outdated Electron framework

The main Xunlei application is based on the Electron framework. This means that its user interface is written in HTML and displayed via the Chromium web browser (renderer process). And here again it’s somewhat of a concern that the Electron version used is 83.0.4103.122 (released in June 2020). It can be expected to share most of the security vulnerabilities with a similarly old Chromium browser.

Granted, an application like that should be less exposed than a web browser as it won’t just load any website. But it does work with remote websites, so vulnerabilities in the way it handles web content are an issue.

Cross-site scripting vulnerabilities

Being HTML-based, the Xunlei application is potentially vulnerable to cross-site scripting vulnerabilities. For most part, this is mitigrated by using the React framework. React doesn’t normally work with raw HTML code, so there is no potential for vulnerabilities here.

Well, normally. Unless dangerouslySetInnerHTML property is being used, which you should normally avoid. But it appears that Xunlei developers used this property in a few places, and now they have code displaying messages like this:

$createElement("div", {

staticClass: "xly-dialog-prompt__text",

domProps: { innerHTML: this._s(this.options.content) }

})

If message content ever happens to be some malicious data, it could create HTML elements that will result in execution of arbitrary JavaScript code.

How would malicious data end up here? Easiest way would be via the browser. There is for example the MessageBoxConfirm native function that could be called like this:

native.CallNativeFunction("MessageBoxConfirm", JSON.stringify({

title: "Hi",

content: `<img src="x" onerror="alert(location.href)">`,

type: "info",

okText: "Ok",

cancelVisible: false

}));

When executed on a “trusted” website in the Xunlei browser, this would make the main application display a message and, as a side-effect, run the JavaScript code alert(location.href).

当在迅雷浏览器中的“受信任”网站上执行时,这将使主应用程序显示一条消息,并且作为副作用,运行JavaScript代码 alert(location.href) 。

Impact of executing arbitrary code in the renderer process

在渲染器进程中执行任意代码的影响

Electron normally sandboxes renderer processes, making certain that these have only limited privileges and vulnerabilities are harder to exploit. This security mechanism is active in the Xunlei application.

Electron 通常对渲染器进程进行沙箱处理,确保这些进程只有有限的权限,并且漏洞更难被利用。此安全机制在迅雷应用程序中处于活动状态。

However, Xunlei developers at some point must have considered it rather limiting. After all, their user interface needed to perform lots of operations. And providing a restricted interface for each such operation was too much effort.

然而,迅雷的开发者一定在某个时候认为它有一定的局限性。毕竟,他们的用户界面需要执行大量操作。为每个此类操作提供受限接口太费力了。

So they built a generic interface into the application. By means of messages like AR_BROWSER_REQUIRE or AR_BROWSER_MEMBER_GET, the renderer process can instruct the main (privileged) process of the application to do just about anything.

因此,他们在应用程序中构建了一个通用接口。通过像 or AR_BROWSER_MEMBER_GET 这样的 AR_BROWSER_REQUIRE 消息,渲染器进程可以指示应用程序的主(特权)进程执行任何操作。

My proof-of-concept exploit successfully abused this interface by loading Electron’s shell module (not accessible to sandboxed renderers by regular means) and calling one of its methods. In other words, the Xunlei application managed to render this security boundary completely useless.

我的概念验证漏洞通过加载 Electron 的 shell 模块(沙盒渲染器无法通过常规方式访问)并调用其方法之一,成功地滥用了这个接口。换句话说,迅雷应用程序设法使这个安全边界完全无用。

The (lack of) fixes

Looking at Xunlei Accelerator 12.0.8.2392, I could not recognize any improvements in this area. The application is still based on Electron 83.0.4103.122. The number of potential XSS vulnerabilities in the message rendering code didn’t change either.

It appears that Xunlei called it a day after making certain that triggering messages with arbitrary content became more difficult. I doubt that it is impossible however.

The XLLite application

Overview of the application

The XLLite application is one of the plugins running within the Xunlei framework. Given that I never created a Xunlei account to see this application in action, my understanding of its intended functionality is limited. Its purpose however appears to be integrating the Xunlei cloud storage into the main application.

As it cannot modify the main application’s user interface directly, it exposes its own user interface as a local web server, on a randomly chosen port between 10500 and 10599. That server essentially provides static files embedded in the application, all functionality is implemented in client-side JavaScript.

Privileged operations are provided by a separate local server running on port 21603. Some of the API calls exposed here are handled by the application directly, others are forwarded to the main application via yet another local server.

I originally got confused about how the web interface accesses the API server, with the latter failing to implement CORS correctly – OPTION requests don’t get a correct response, so that only basic requests succeed. It appears that Xunlei developers didn’t manage to resolve this issue and instead resorted to proxying the API server on the user interface server. So any endpoints available on the API server are exposed by the user interface server as well, here correctly (but seemingly unnecessarily) using CORS to allow access from everywhere.

So the communication works like this: the Xunlei application loads http://127.0.0.1:105xx/ in a frame. The page then requests some API on its own port, e.g. http://127.0.0.1:105xx/device/now. When handling the request, the XLLite application requests http://127.0.0.1:21603/device/now internally. And the API server handler within the same process responds with the current timestamp.

所以通信的工作原理是这样的:迅雷应用程序在一个帧中加载 http://127.0.0.1:105xx/ 。然后,该页面在自己的端口上请求一些 API,例如 http://127.0.0.1:105xx/device/now .处理请求时,XLLite 应用程序在内部请求 http://127.0.0.1:21603/device/now 。同一进程中的 API 服务器处理程序使用当前时间戳进行响应。

This approach appears to make little sense. However, it’s my understanding that Xunlei also produces storage appliances which can be installed on the local network. Presumably, these appliances run identical code to expose an API server. This would also explain why the API server is exposed to the network rather than being a localhost-only server.

这种方法似乎没有多大意义。但是,据我所知,迅雷也生产可以安装在本地网络上的存储设备。据推测,这些设备运行相同的代码来公开 API 服务器。这也可以解释为什么 API 服务器向网络公开,而不是仅是本地主机服务器。

The “pan authentication”

“泛身份验证”

With quite a few API calls having the potential to do serious damage or at the very least expose private information, these need to be protected somehow. As mentioned above, Xunlei developers chose not to use CORS to restrict access but rather decided to expose the API to all websites. Instead, they implemented their own “pan authentication” mechanism.

由于相当多的 API 调用可能会造成严重损害或至少暴露私人信息,因此需要以某种方式保护这些调用。如上所述,迅雷开发者选择不使用 CORS 来限制访问,而是决定将 API 暴露给所有网站。相反,他们实现了自己的“泛身份验证”机制。

Their approach of generating authentication tokens was taking the current timestamp, concatenating it with a long static string (hardcoded in the application) and hashing the result with MD5. Such tokens would expire after 5 minutes, apparently an attempt to thwart replay attacks.

他们生成身份验证令牌的方法是获取当前时间戳,将其与长静态字符串(在应用程序中硬编码)连接起来,并使用 MD5 对结果进行哈希处理。此类令牌将在 5 分钟后过期,显然是为了阻止重放攻击。

They even went as far as to perform time synchronization, making sure to correct for deviation between the current time as perceived by the web page (running on the user’s computer) and by the API server (running on the user’s computer). Again, this is something that probably makes sense if the API server can under some circumstances be running elsewhere on the network.

他们甚至执行时间同步,确保纠正网页(在用户计算机上运行)和 API 服务器(在用户计算机上运行)感知到的当前时间之间的偏差。同样,如果 API 服务器在某些情况下可以在网络上的其他地方运行,这可能是有意义的。

Needless to say that this “authentication” mechanism doesn’t provide any value beyond very basic obfuscation.

Achieving code execution via plugin installation

There are quite a few interesting API calls exposed here. For example, the device/v1/xllite/sign endpoint would sign data with one out of three private RSA keys hardcoded in the application. I don’t know what this functionality is used for, but I sincerely hope that it’s as far away from security and privacy topics as somehow possible.

There is also the device/v1/call endpoint which is yet another way to open a page in the Xunlei browser. Both OnThunderxOpt and OpenNewTab calls allow that, the former taking a thunderx:// address to be processed and the latter a raw page address to be opened in the browser.

It’s fairly obvious that the API exposes full access to the user’s cloud storage. I chose to focus my attention on the drive/v1/app/install endpoint however, which looked like it could do even more damage. This endpoint in fact turned out to be a way to install binary plugins.

I couldn’t find any security mechanisms preventing malicious software to be installed this way, apart from the already mentioned useless “pan authentication.” However, I couldn’t find any actual plugins to use as an example. In the end I figured out that a plugin had to be packaged in an archive containing a manifest.yaml file like the following:

ID: Exploit

Title: My exploit

Description: This is an exploit

Version: 1.0.0

System:

- OS: windows

ARCH: 386

Service:

ExecStart: Exploit.exe

ExecStop: Exploit.exe

The plugin would install successfully under Thunder\Profiles\XLLite\plugin\Exploit\1.0.1\Exploit but the binary wouldn’t execute for some reason. Maybe there is a security mechanism that I missed, or maybe the plugin interface simply isn’t working yet.

Either way, I started thinking: what if instead of making XLLite run my “plugin” I would replace an existing binary? It’s easy enough to produce an archive with file paths like ..\..\..\oops.exe. However, the Go package archiver used here has protection against such path traversal attacks.

The XLLite code deciding which folder to put the plugin into didn’t have any such protections on the other hand. The folder is determined by the ID and Version values of the plugin’s manifest. Messing with the former is inconvenient, it being present twice in the path. But setting the “version” to something like ..\..\.. achieved the desired results.

另一方面,决定将插件放入哪个文件夹的 XLLite 代码没有任何此类保护。文件夹由插件清单的 ID 和 Version 值确定。弄乱前者很不方便,它在路径中出现两次。但是将“版本”设置为类似 ..\..\.. 的东西达到了预期的结果。

Two complications: 两种并发症:

- The application to be replaced cannot be running or the Windows file locking mechanism will prevent it from being replaced.

要替换的应用程序无法运行,否则 Windows 文件锁定机制将阻止其被替换。 - The plugin installation will only replace entire folders.

插件安装只会替换整个文件夹。

In the end, I chose to replace Xunlei’s media player for my proof of concept. This one usually won’t be running and it’s contained in a folder of its own. It’s also fairly easy to make Xunlei run the media player by using a thunderx:// link. Behold, installation and execution of a malicious application without any user interaction.

最后,我选择用迅雷的媒体播放器来代替我的概念验证。这个通常不会运行,它包含在自己的文件夹中。使用 thunderx:// 链接让 Xunlei 运行媒体播放器也相当容易。看,在没有任何用户交互的情况下安装和执行恶意应用程序。

Remember that the API server is exposed to the local network, meaning that any devices on the network can also perform API calls. So this attack could not merely be executed from any website the user happened to be visiting, it could also be launched by someone on the same network, e.g. when the user is connected to a public WiFi.

请记住,API 服务器向本地网络公开,这意味着网络上的任何设备也可以执行 API 调用。因此,这种攻击不仅可以从用户碰巧访问的任何网站执行,还可以由同一网络上的某个人发起,例如,当用户连接到公共WiFi时。

The fixes 修复

As of version 3.19.4 of the XLLite plugin (built January 25, 2024 according to its digital signature), the “pan authentication” method changed to use JSON Web Tokens. The authentication token is embedded within the main page of the user interface server. Without any CORS headers being produced for this page, the token cannot be extracted by other web pages.

从 XLLite 插件的 3.19.4 版本(根据其数字签名于 2024 年 1 月 25 日构建)开始,“pan authentication”方法更改为使用 JSON Web 令牌。身份验证令牌嵌入在用户界面服务器的主页中。如果不为此页面生成任何 CORS 标头,则其他网页无法提取令牌。

It wasn’t immediately obvious what secret is being used to generate the token. However, authentication tokens aren’t invalidated if the Xunlei application is restarted. This indicates that the secret isn’t being randomly generated on application startup. The remaining possibilities are: a randomly generated secret stored somewhere on the system (okay) or an obfuscated hardcoded secret in the application (very bad).

While calls to other endpoints succeed after adjusting authentication, calls to the drive/v1/app/install endpoint result in a “permission denied” response now. I did not investigate whether the endpoint has been disabled or some additional security mechanism has been added.

Plugin management

The oddities

XLLite’s plugin system is actually only one out of at least five completely different plugin management systems in the Xunlei application. One other is the main application’s plugin system, the XLLite application is installed as one such plugin. There are more, and XLLiveUpdateAgent.dll is tasked with keeping them updated. It will download the list of plugins from an address like http://upgrade.xl9.xunlei.com/plugin?os=10.0.22000&pid=21&v=12.0.3.2240&lng=0804 and make sure that the appropriate plugins are installed.

Note the lack of TLS encryption here which is quite typical. Part of the issue appears to be that Xunlei decided to implement their own HTTP client for their downloads. In fact, they’ve implemented a number of different HTTP clients instead of using any of the options available via the Windows API for example. Some of these HTTP clients are so limited that they cannot even parse uncommon server responses, much less support TLS. Others support TLS but use their own list of CA certificates which happens to be Mozilla’s list from 2016 (yes, that’s almost eight years old).

请注意,这里缺少 TLS 加密,这是非常典型的。部分问题似乎是迅雷决定为他们的下载实现自己的HTTP客户端。事实上,他们已经实现了许多不同的 HTTP 客户端,而不是使用 Windows API 提供的任何选项。其中一些 HTTP 客户端非常有限,甚至无法解析不常见的服务器响应,更不用说支持 TLS。其他人支持TLS,但使用他们自己的CA证书列表,这恰好是Mozilla从2016年开始的列表(是的,这几乎是八年前的)。

Another common issue is that almost all these various update mechanisms run as part of the regular application process, meaning that they only have user’s privileges. How do they manage to write to the application directory then? Well, Xunlei solved this issue: they made the application directory writable with user’s privileges! Another security mechanism successfully dismantled. And there is a bonus: they can store application data in the same directory rather than resorting to per-user nonsense like AppData.

另一个常见问题是,几乎所有这些不同的更新机制都作为常规应用程序流程的一部分运行,这意味着它们只有用户的权限。那么他们如何设法写入应用程序目录呢?那么,迅雷解决了这个问题:他们用用户的权限使应用程序目录可写!另一个安全机制被成功拆除。还有一个好处:他们可以将应用程序数据存储在同一个目录中,而不是像 AppData 那样诉诸于每个用户的废话。

Altogether, you better don’t run Xunlei Accelerator on untrusted networks (meaning: any of them?). Anyone on your network or anyone who manages to insert themselves into the path between you and the Xunlei update server will be able to manipulate the server response. As a result, the application will install a malicious plugin without you even noticing anything.

总而言之,你最好不要在不受信任的网络上运行迅雷加速器(意思是:其中任何一个?您网络上的任何人或设法将自己插入您和迅雷更新服务器之间的路径的任何人都将能够操纵服务器响应。因此,该应用程序将安装恶意插件,而您甚至不会注意到任何事情。

You also better don’t run Xunlei Accelerator on a computer that you share with other people. Anyone on a shared computer will be able to add malicious components to the Xunlei application, so next time you run it your user account will be compromised.

您最好不要在与其他人共享的计算机上运行迅雷加速器。共享计算机上的任何人都可以向 Xunlei 应用程序添加恶意组件,因此下次运行它时,您的用户帐户将受到威胁。

Example scenario: XLServicePlatform

示例方案:XLServicePlatform

I decided to focus on XLServicePlatform because, unlike all the other plugin management systems, this one runs with system privileges. That’s because it’s a system service and any installed plugins will be loaded as dynamic libraries into this service process. Clearly, injecting a malicious plugin here would result in full system compromise.

我决定专注于 XLServicePlatform,因为与所有其他插件管理系统不同,这个系统以系统权限运行。这是因为它是一个系统服务,任何已安装的插件都将作为动态库加载到此服务进程中。显然,在这里注入恶意插件会导致整个系统受到损害。

The management service downloads the plugin configuration from http://plugin.pc.xunlei.com/config/XLServicePlatform_12.0.3.xml. Yes, no TLS encryption here because the “HTTP client” in question isn’t capable of TLS. So anyone on the same WiFi network as you for example could redirect this request and give you a malicious response.

In fact, that HTTP client was rather badly written, and I found multiple Out-of-Bounds Read vulnerabilities despite not actively looking for them. It was fairly easy to crash the service with an unexpected response.

But it wasn’t just that. The XML response was parsed using libexpat 2.1.0. With that version being released more than ten years ago, there are numerous known vulnerabilities, including a number of critical remote code execution vulnerabilities.

I generally leave binary exploitation to other people however. Continuing with the high-level issues, a malicious plugin configuration will result in a DLL or EXE file being downloaded, yet it won’t run. There is a working security mechanism here: these files need a valid code signature issued to Shenzhen Thunder Networking Technologies Ltd.

But it still downloads. And there is our old friend: a path traversal vulnerability. Choosing the file name ..\XLBugReport.exe for that plugin will overwrite the legitimate bug reporter used by the Xunlei service. And crashing the service with a malicious server response will then run this trojanized bug reporter, with system privileges.

但它仍然下载。还有我们的老朋友:路径遍历漏洞。选择该插件的文件名 ..\XLBugReport.exe 将覆盖 Xunlei 服务使用的合法 bug 报告器。然后,使用恶意服务器响应使服务崩溃将运行此具有系统权限的特洛伊木马错误报告程序。

My proof of concept exploit merely created a file in the C:\Windows directory, just to demonstrate that it runs with sufficient privileges to do it. But we are talking about complete system compromise here.

我的概念验证漏洞只是在目录中 C:\Windows 创建了一个文件,只是为了证明它以足够的权限运行。但我们在这里谈论的是完整的系统妥协。

The (lack of?) fixes

(缺少?)修复

At the time of writing, XLServicePlatform still uses its own HTTP client to download plugins which still doesn’t implement TLS support. Server responses are still parsed using libexpat 2.1.0. Presumably, the Out-of-Bounds Read and Path Traversal vulnerabilities have been resolved but verifying that would take more time than I am willing to invest.

在撰写本文时,XLServicePlatform 仍然使用自己的 HTTP 客户端来下载插件,这些插件仍然没有实现 TLS 支持。服务器响应仍使用 libexpat 2.1.0 进行解析。据推测,越界读取和路径遍历漏洞已得到解决,但验证这一点需要的时间比我愿意投入的时间还要多。

The application will still render its directory writable for all users. It will also produce a number of unencrypted HTTP requests, including some that are related to downloading application components.

应用程序仍将使其目录可写给所有用户。它还将生成许多未加密的 HTTP 请求,包括一些与下载应用程序组件相关的请求。

Outdated components 过时的组件

I’ve already mentioned the browser being based on an outdated Chromium version, the main application being built on top of an outdated Electron platform and a ten years old XML library being widely used throughout the application. This isn’t by any means the end of it however. The application packages lots of third-party components, and the general approach appears to be that none of them are ever updated.

我已经提到过该浏览器基于过时的 Chromium 版本,主应用程序构建在过时的 Electron 平台之上,并且在整个应用程序中广泛使用了一个十年前的 XML 库。然而,这绝不是它的结束。应用程序打包了许多第三方组件,一般方法似乎是它们都不会更新。

Take for example the media player XMP a.k.a. Thunder Video which is installed as part of the application and can be started via a thunderx:// address from any website. This is also an Electron-based application, but it’s based on an even older Electron 59.0.3071.115 (released in June 2017). The playback functionality seems to be based on the APlayer SDK which Xunlei provides for free for other applications to use.

Now you might know that media codecs are extremely complicated pieces of software that are known for disastrous security issues. That’s why web browsers are very careful about which media codecs they include. Yet APlayer SDK features media codecs that have been discontinued more than a decade ago as well as some so ancient that I cannot even figure out who developed them originally. There is FFmpeg 2021-06-30 (likely a snapshot around version 4.4.4), which has dozens of known vulnerabilities. There is libpng 1.0.56, which was released in July 2011 and is affected by seven known vulnerabilities. Last but not least, there is zlib 1.2.8-4 which was released in 2015 and is affected by at least two critical vulnerabilities. These are only some examples.

So there is a very real threat that Xunlei users might get compromised via a malicious media file, either because they were tricked into opening it with Xunlei’s video player, or because a website used one of several possible ways to open it automatically.

As of Xunlei Accelerator 12.0.8.2392, I could not notice any updates to these components.

Reporting the issues 报告问题

Reporting security vulnerabilities is usually quite an adventure, and the language barrier doesn’t make it any better. So I was pleasantly surprised to discover XunLei Security Response Center that was even discoverable via an English-language search thanks to the site heading being translated.

报告安全漏洞通常是一次冒险,语言障碍并没有让它变得更好。因此,我惊喜地发现迅雷安全响应中心甚至可以通过英语搜索找到,这要归功于网站标题的翻译。

Unfortunately, there was a roadblock: submitting a vulnerability is only possible after logging in via WeChat or QQ. While these social networks are immensely popular in China, creating an account from outside China proved close to impossible. I’ve spent way too much time on verifying that.

不幸的是,有一个障碍:只有通过微信或QQ登录后才能提交漏洞。虽然这些社交网络在中国非常受欢迎,但事实证明,在中国境外创建一个账户几乎是不可能的。我花了太多时间来验证这一点。

That’s when I took a closer look and discovered an email address listed on the page as fallback for people who are unable to log in. So I’ve sent altogether five vulnerability reports on 2023-12-06 and 2023-12-07. The number of reported vulnerabilities was actually higher because the reports typically combined multiple vulnerabilities. The reports mentioned 2024-03-06 as publication deadline.

就在那时,我仔细查看了一下,发现了页面上列出的电子邮件地址,作为无法登录的人的后备。因此,我在 2023-12-06 和 2023-12-07 总共发送了五份漏洞报告。报告的漏洞数量实际上更高,因为报告通常合并了多个漏洞。报告提到 2024-03-06 为出版截止日期。

I received a response a day later, on 2023-12-08:

一天后,我在 2023-12-08 收到了回复:

Thank you very much for your vulnerability submission. XunLei Security Response Center has received your report. Once we have successfully reproduced the vulnerability, we will be in contact with you.

非常感谢您提交漏洞。迅雷安全响应中心已收到您的报告。一旦我们成功重现了该漏洞,我们将与您联系。

Just like most companies, they did not actually contact me again. I saw my proof of concept pages being accessed, so I assumed that the issues are being worked on and did not inquire further. Still, on 2024-02-10 I sent a reminder that the publication deadline was only a month away. I do this because in my experience companies will often “forget” about the deadline otherwise (more likely: they assume that I’m not being serious about it).

就像大多数公司一样,他们实际上没有再联系我。我看到我的概念验证页面被访问,所以我认为这些问题正在处理中,没有进一步询问。尽管如此,在 2024 年 2 月 10 日,我还是提醒说,距离出版截止日期只有一个月的时间。我这样做是因为根据我的经验,公司经常会“忘记”截止日期(更有可能的是:他们认为我没有认真对待它)。

I received another laconic reply a week later which read:

一周后,我收到了另一封简洁的回复,上面写着:

XunLei Security Response Center has verified the vulnerabilities, but the vulnerabilities have not been fully repaired.

迅雷安全响应中心已对漏洞进行了验证,但漏洞尚未完全修复。

That was the end of the communication. I don’t really know what Xunlei considers fixed and what they still plan to do. Whatever I could tell about the fixes here has been pieced together from looking at the current software release and might not be entirely correct.

通信到此结束。我真的不知道 Xunlei 认为修复了什么,以及他们仍然打算做什么。 关于这里的修复,我能说的是什么,都是通过查看当前的软件版本拼凑起来的,可能并不完全正确。

It does not appear that Xunlei released any further updates in the month after this communication. Given the nature of the application with its various plugin systems, I cannot be entirely certain however.

迅雷似乎没有在这次沟通后的一个月内发布任何进一步的更新。但是,鉴于该应用程序及其各种插件系统的性质,我不能完全确定。

原文始发于Almost Secure:Numerous vulnerabilities in Xunlei Accelerator application